You step out into the street. Suddenly, you notice a car speeding toward you. Just in time, you move out of the way and into safety. Your brain, constantly monitoring situations has acted almost instantly to protect you.

This protective action is possible due to the way our brains have developed to respond over time. The older part of our brain is designed to help us in “survival mode” and focuses on preparing our bodies to fight, freeze, or flee. The newer part of our brain allows us to think logically, process emotions, problem-solve, and be self-aware. When our brains detect threat, the newer part of the brain goes “offline” and the older part of our brain takes control. Once we respond to the threat, our newer brain comes back online and we are again able to communicate and think flexibly, creatively, and rationally.

In terms of a speeding car, this process is obviously very useful. Sometimes, however, we perceive a situation that is not actually threatening in the same way. Think about that example of narrowly avoiding a speeding car. Close your eyes and imagine the sensations you would feel. Your heart might beat much faster than normal. Maybe you feel short of breath, dizzy, sweaty, or sick to your stomach. These are reactions our bodies have developed to keep us safe and alert and are very normal. Now imagine feeling these sensations when you are looking at a test or a crowded room full of people instead of an oncoming car. That’s anxiety.

These perceptions lead to us to feel tense, irritable, restless, tired, or shaky. Often, it can be difficult to concentrate, focus, and fall or stay asleep. When feeling anxious, we might not even notice some of our symptoms, because we are focused on what we think is happening or fear might happen. These perceptions can be disruptive in any setting – at home, at school, with friends and family. With school, this might mean we shut down during a test we prepared for or can’t fall asleep because we can’t stop thinking about the next day. Socially, we might stop doing things we used to enjoy, avoiding hanging out in groups, or responding to texts because it feels too overwhelming. When our fear or worry significantly interferes with our daily life, we describe it as anxiety.

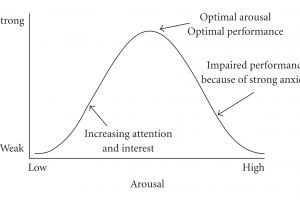

It’s important to note here that a little bit of academic or social anxiety can be helpful. For those of you who like psychology, this is known as the Yerkes-Dodson Law and looks like this:

It’s important to note here that a little bit of academic or social anxiety can be helpful. For those of you who like psychology, this is known as the Yerkes-Dodson Law and looks like this:

The middle of this curve is where we do our best work, nail our performances, or even ask someone out on a date. Clinical anxiety kicks in to the right of the curve. If you find yourself to the right of the curve often (and you’re not just running around dodging cars on Mopac,), I’d recommend talking to a professional because there are many ways to manage anxiety – with and without medication.

I love working with anxiety because we can really bring a lot of creativity to the process. It’s always helpful to start with what’s already working (maybe just a little bit) and build on it. For example, you might notice a greater sense of calm when your favorite song is playing. From there, we can build a playlist to turn on when studying for that test. Maybe you are artistic and enjoy the feel of oil pastels on paper when your heart starts racing. We can create an art journal to explore ways to cope expressively. There are also wonderful ways to help our brains come back online once they’ve gone into fear mode – through breathing, mindfulness, progressive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery. In addition to coping strategies, it is important to explore those fears, thoughts, and things we say to ourselves when we feel anxious. When we name these fears in a safe space and develop an understanding of what’s involved, we can discover new tools to manage these feelings.